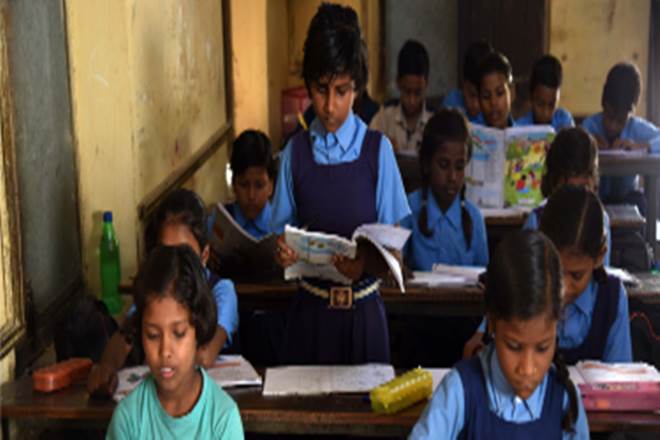

The government has released a draft of the much-awaited New Education Policy (NEP) for comments. This policy, like many before it, provides a macro overview of a host of things the government wants to accomplish. In a sense, it is a list of ‘what’ the government wants to do, but missing in the NEP, as with much policy thinking, is the critical ‘how’. Only when a policy appreciates or addresses the complexity of the ‘how’can it have a clear and focused view of the ‘what’. Just as the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan and RTE Act were targeted measures to address the issue of access to elementary education, the government needs a similar approach to improve the quality of education.

A systemic approach to transforming school education can substantially alter the education ecosystem for the better. Such an approach entails both academic and governance reforms. The problems plaguing the system range from those related to pedagogy, such as inordinate focus on syllabus completion rather than grade-competency, poorly-designed assessments, cascaded teacher training mechanism, and administrative issues such as inefficient review and monitoring mechanisms, inefficient mechanism for scheme delivery, and lack of data availability for right decision making.

Systemic approach: At the core of this is improving learning outcomes. First, shift focus from syllabus completion to making students grade-competent, i.e. ensuring they can comprehend learning material appropriate to their grade. Second, ensure that regular, standardised assessments are administered across all schools in a state which test students on these competencies. Performance data from these assessments should be available in an easy-to-comprehend manner for all stakeholders. This is critical to benchmark performance and allow teachers to take corrective action. Third, to address the issue of thousands of children not being grade-competent, state-wide, structured remedial or practice workbook programmes are necessary.

Critical to the implementation of these academic reforms is strengthening human capital and administrative systems. The former entails ensuring that adequate number of teachers are available in classrooms as well as providing them with the tools necessary to teach better, including timely, need-based training. The latter includes consolidating unviable, small schools into larger schools for efficient utilisation of resources (human and physical), and using technology and data to increase administrative efficiency.

Effective implementation of these reforms rests on driving accountability, not just among teachers but the entire administrative machinery that constitutes the education system. Finally, the kind of reforms that are needed to overhaul the education system cannot happen without the political and bureaucratic leadership of states pushing for these changes from the top.

Implementing systemic reforms: The framework described above is not meant to be theory. It has been developed based on the experience of states such as Andhra Pradesh, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh that have adopted a systemic approach to transforming education. To get a better sense of how the systemic approach works, let’s look at the reforms these states have undertaken.

All 8,556 primary government schools in Haryana conduct remedial classes for 10 lakh students during the first 45 minutes of the school day, with the schedule of lessons aligned to the content taught in the classroom. To fix accountability, Haryana has developed an Academic Monitoring System that keeps a check on all stakeholders (teachers, block and state officials). Monitoring officials regularly visit schools to observe classroom transactions, teaching methods, assess student performance and implementation of the remedial programme. Their insights are recorded on an Academic Monitoring Dashboard that is used during review meetings. The Saksham Ghoshna campaign puts the onus of achieving a specific target (in terms of a benchmark for grade-competence) on blocks, and devolves ownership and accountability from the state to teachers, district and block officials. Through third-party assessment, blocks are declared ‘Saksham’ if more than 80% students are grade-competent.

In 2016, Himachal became the first state to ensure delivery of textbooks to 6 lakh students in 15,000 schools before the start of the academic year. Overcoming constraints of weather and terrain, the state’s Department of Elementary Education worked with the Himachal Pradesh Board of School Education to streamline the supply chain of textbook delivery by using technological solutions to introduce speed, efficiency and transparency. Since 2016, the state has ensured timely delivery of textbooks every year. Himachal has also been at the forefront of adopting technology to improve the quality of training provided to teachers. In-person teacher training is an annual exercise in all states. While useful, this training is not sufficient. To address this, Himachal Pradesh collaborated with a firm that provides training content for teachers through a mobile app.

Andhra has set up a central assessment cell that designs and administers standardised assessments across the state to 25 lakh students. The results of these assessments are uploaded on an assessment dashboard, integrated with the CM’s dashboard, within 10-12 days. This ensures timely availability of critical information on student performance to all stakeholders. Gnana Dhaara, a summer residential remedial programme in Andhra, is organised for students of classes 6 and 10 in government schools.

Way forward: The new government must prioritise implementation as much as, if not more than, developing new policies. It should encourage states to constitute an outcome-focused programme management to learn from the systemic approach taken by some states. The HRD ministry can then encourage more states to embark on their own journey of systemic education transformation. A targeted strategy, rather than piecemeal interventions, can go a long way in sustainably improving learning levels of students.

[“source=financialexpress”]