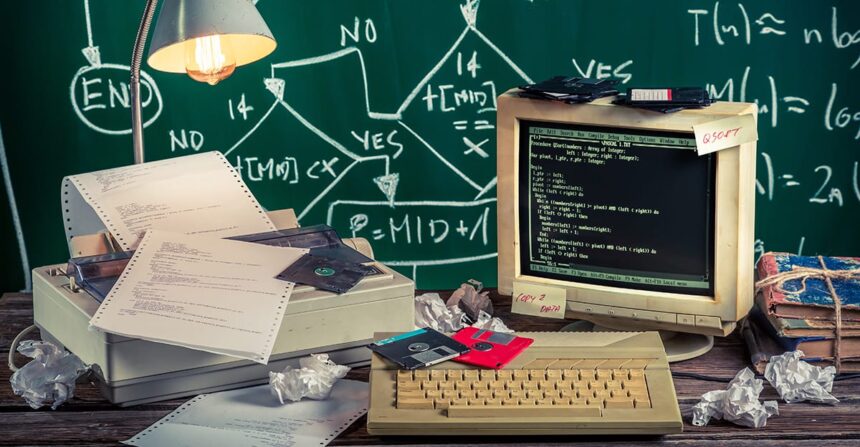

In 2025, designing great user experiences isn’t just about embracing what’s new — it’s about questioning what’s necessary. Many designers are beginning to look backward as the complexity and automation of digital products increase. Once thought to be out of date, analog devices now provide rare clarity. We are reminded by mechanical radios, cameras, and tape recorders that simple is not primitive. It’s accurate. Although innovation frequently encourages us to add, the real skill may be the ability to subtract. Why We Still Learn from Outdated Technologies Analog devices were built in a world without updates or overlays. Their interfaces needed to be intuitive right away. You could hear sound by turning a knob. You snapped a picture after pressing the shutter. There is no FAQ or walkthrough. The interface itself was the learning curve. “Good design is as little design as possible,” according to Dieter Rams. This doesn’t mean bare or boring. It means distilled — stripped down to only what the user actually needs.

Reviving fundamental analog principles is important: One input, one function. There was no multifunctionality hidden behind long-presses or swipe directions.

Transparent physical feedback Every action felt like something—a click, a snap, resistance. Instantaneous cause and effect. The outcome of each action was visible, audible, or tactile.

Modern interfaces often abandon these ideas in the name of flexibility, which sounds empowering — until the user gets lost in menus and settings. Analog tools made it hard to get confused. That is user respect, not a backward step. Mechanical Cameras: Design-Based Discipline SLR cameras are masterworks of clarity in interaction. They make no effort to be smart. They don’t guess what you want. They just give you the controls and let you make your own decision. And that is precisely why using them makes you feel good. Donald Norman, in The Design of Everyday Things:

“When the affordances are perceptible, they offer strong clues to the operations of things.”

Options are not hidden by these cameras; rather, they are the options. The interface is the product.

Lessons from classic camera UX:

Each core setting (ISO, aperture, shutter) had its own control. Mastery was possible because functions were separated. The skill was taught by the body. Instead of reading, you learned by touching. Experimentation was rewarded by design. Nothing was disrupted by errors.

Contents

They revealed something

The self-assurance of an SLR feels radical in a time when even basic photo apps offer auto modes, filters, and AI corrections. Nostalgia as Signal, Not Decoration

The analog revival isn’t just hipster marketing. Users are gravitating back to single-purpose tools — Kindle readers, vinyl records, flip phones — not because they’re cool, but because they’re calm. They don’t distract. They don’t try to be all things to everyone. Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice:

“Too many choices can overwhelm and paralyze, not liberate.”

This is evident in UX patterns: Apps that excel in a single area are flourishing. Think Bear (note-taking), Oura (sleep tracking), or Focus Keeper (timers). Trust is built through minimally altered interfaces over time. Have you ever attempted to reuse an application after a redesign that broke everything? That’s why people stick with old tools.

It’s back to deliberate friction. Manual control, confirmation steps, and even limited customization are seen as thoughtful, not frustrating.

The takeaway is crystal clear: simplicity is not passé. It’s what many users quietly prefer.

Best Practices for UX Designers You don’t need to design like it’s 1985. But you can apply those principles right now — especially if you’re building for clarity, focus, or trust.

In digital projects, apply analog discipline: Actions map controls 1:1. Avoid multifunction buttons unless necessary.

Create tangible prototypes. Problems with interaction can be seen in models made of paper or cardboard. Make strong defaults, not pliable ones. Give users confidence without needing to tweak.

Avoid “settings sprawl.” If your config screen is a maze, you’ve offloaded too much complexity.

Where they add meaning, use physical metaphors. Sliders, toggles, and rotary selectors still apply digitally to tactile logic. Measure comprehension rather than performance: Without reading, can users guess what each control does? Can a novice perform the task without assistance?

What happens when users fail — is recovery obvious and forgiving?

The Benefits of Doing Less With More Fast isn’t always a sign of good UX. It means self-assurance. When it came to analog tools, such as winding a film camera or tuning a dial, users had complete control despite their preference for slowness. The mental presence that most digital tools lack was provided by that deliberate pace. By accepting limitations, the best digital interfaces of today mimic this: Kindle limits what you can do — so you focus on reading.

Apps for budgeting don’t tell you what you’ll spend, but they do let you keep track of it. Writing tools that don’t distract you remove all formatting so that the words come first. These products succeed not because they’re powerful, but because they’re focused. That’s an analog lesson worth remembering.

Moving Forward from the Past The future of UX isn’t just about what we can do — it’s about what we should stop doing. We no longer require additional interfaces that change weekly, conceal features with swipes, or guess what users want. We need tools that behave predictably, communicate clearly, and trust users with real control.

Analog technology didn’t hold us back. It taught us what matters.

Designers who embrace this mindset — who ask “How would this work if it were physical?” — will lead a wave of digital products that feel grounded, not overwhelming. Not retro. Not nostalgic. Just right.