The analysis, carried out by London Economics on behalf of the Higher Education Policy Institute and Kaplan International, looks at how the depreciation of the pound, changes to EU student fees and funding and student visa policy could impact international student numbers and tuition fee revenue.

“We need not only to not have new restrictions on international students, but also to make it abundantly clear that the UK is open”

Raising EU student fees to match those paid by non-EU students and removing EU students’ access to public loan and grant funding – the likely post-Brexit scenario predicted by many educators – could mean EU student numbers drop by as much as 57%, the study found.

This drop represents a loss of some 31,000 students and £40m in lost income for universities, after accounting for the fee increase.

Increasing fees for EU students would also affect the demographics of incoming students.

“If you remove student support and raise fees to international levels, the only EU students that will be able to come to the UK is those that have accumulated cash reserves,” commented Gavan Conlon, leader of the education and labour market team at London Economics.

The outlook for non-EU enrolments at UK universities, meanwhile, looks more optimistic. Rising non-EU numbers could offset the drop in EU students if the value of the pound continues to depreciate, the study asserts.

It calculates that a 10% decrease in the value of the sterling could trigger a corresponding 9% increase in enrolments from outside of the UK in the first year. That increase amounts to 20,000 more students on UK campuses, almost three-quarters of whom would come from outside Europe, which would bring in an additional £227m in tuition fees.

Overall, the modelling estimates that a golden trifecta of fee harmonisation, the removal of EU student support and sterling depreciation could result in a net £187m increase in tuition fee income in the first year, though the financial impact on different universities could vary greatly.

Oxford and Cambridge could each be £11m better off if these three factors align, with higher EU student fees and growth in international enrolments offsetting any loss of EU students.

On the other hand, many younger institutions could stand to lose around £100,000 a year in fee income. But, “it is unclear that these financial gains would be realised,” the study adds.

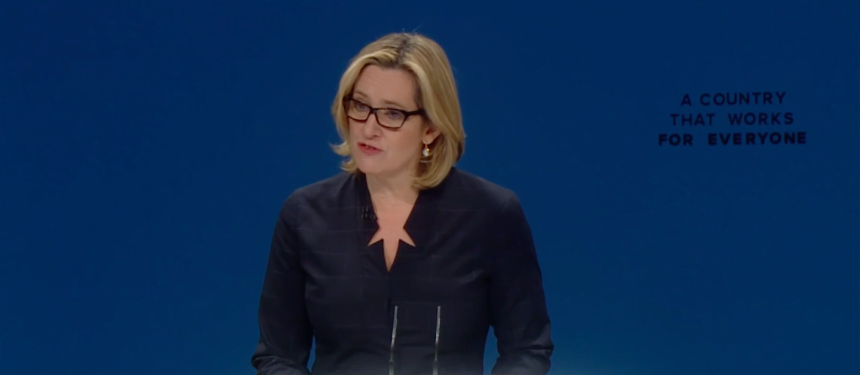

The figures are based on the assumption that Home Office policy affecting international students will remain unchanged – an unlikely outcome, given Home Secretary Amber Rudd’s indications that a further crackdown on student visas is in the pipeline.

If these 20,000 additional students cited in the modelling are not allowed to come to the UK, the country could miss out on £463m in fee income each year, plus an additional £604m in non-tuition fee spending and £928m in indirect and induced effects (the impact on universities’ supply chains).

“If the Home Office has sole control of higher education policy, it will try and stop foreigners coming into the country”

All together, these figures add up to nearly £2bn in lost income.

And the impact could be even greater if the Home Office were to introduce large cuts to student visas, the report warns.

Other factors that could have a material impact on international student numbers include currency fluctuations in source markets and the price of oil.

For example, a 10% bump in the energy price index could lead to a 3.8% rise in incoming students from the world’s top 20 producers of oil, but a 1.1% drop from other countries, it forecasts.

HEPI’s director, Nick Hillman, said the findings show the landscape is “perhaps more rosy than some people have pictured it” but nonetheless lend urgency to calls for policy that welcomes international talent.

“If we’re not to lose out on this £2bn, then we need not only to not have new restrictions on international students… but also to make it abundantly clear that the UK is open and welcoming to people from other countries,” he counselled.

However, arriving at this favourable policy environment seems unlikely in the current climate, he noted.

“If the Home Office has sole control of higher education policy, it will try and stop foreigners coming into the country.

“If you share policy with the foreign office, with the business department, with the education department, with the cabinet office, you have other voices round the table.”

The financial modelling in the report by London Economics is based on historical data on international student enrolment data from HESA and international enrolment and tuition fees data from UNESCO and OECD.

Its calculations take into account macroeconomic data including exchange rates and population size, as well as a variable capturing the removal of the UK’s post-study work visa in 2012.

[Source:- Pienews]